In a previous blog post, we described how a properly implemented code signing system can independently verify that the code being signed matches the code in the source control repository, via a feature called automated hash validation. We further showed how to do all of this without impeding performance.

When such a code signing solution is deployed, attackers are forced to insert their malicious code into the source control repository (thereby making it visible to the organization) and hope it bypasses the analyzer tools to be signed along with the rest of the legitimate code.

This article focuses on additional preventive and detective controls you can layer around the repository and CI/CD pipeline to reduce the risk of malware injection and catch it as early as possible. Topics like developer training, security requirement definition, and repository selection are important, but out of scope here—we’ll cover those in a future post.

Preventing Attacks: Securing Commits to Source Control

Imagine you’re a developer, ready to commit code to the main repository. The first thing you do is connect and authenticate to that repository. This is the first—and arguably most critical—line of defense against unauthorized or malicious code.

Move Beyond Password-Based Access

Just as the industry is moving towards passwordless authentication for web applications, SSH, and more, password-based authentication should be avoided for access to the source control repository.

Instead, enterprises should enforce an access model that combines:

- Multi-factor authentication (MFA)

- Device Authentication,

- Behavior analysis/ anomaly detection

This means an attacker must:

-

Compromise a trusted device

-

Steal both first- and second-factor credentials

-

Evade behavioral detection

…or recruit an insider with legitimate access. Either way, the bar is dramatically higher.

At first glance, this may sound unrealistic unless your repository and client tools natively support these controls. In reality, they already do—just not always in an obvious way.

Use Key-Based Authentication With Remote Key Protection

Most modern source control systems support key-based authentication. Git, for example, supports SSH-based authentication using key pairs.

The default pattern is:

-

Private SSH key is stored on the developer’s workstation

-

SSH client uses this local key to authenticate to the repository

A more secure architecture is:

-

The private key never resides on the workstation

-

The private key is stored in a secure hardware-backed service (e.g., HSM or key manager)

-

Authentication requests are proxied to this service, which generates signatures remotely

In this model, the external signing or key management service can enforce:

-

MFA

-

Device posture and identity checks

-

Behavioral rules and risk-based policies

All of this can be done without modifying the source control server itself or the core Git/SSH workflow.

Enforce Least-Privilege Authorization

After authentication comes authorization—deciding what an authenticated user is allowed to do.

Regardless of the repository platform or its built-in permission model, apply the principle of least privilege:

-

Developers should have read/write access only to repositories they actively need

-

When developers move teams or projects, their repository permissions should be promptly updated

-

CI/CD systems and build servers should have read-only access, scoped to the minimum repositories required

Reducing privilege scope limits how far an attacker—or a compromised account—can move laterally if they gain access.

Require Cryptographic Commit Signing

Many repositories, including Git, support signing commits. If your platform supports it, enforce commit signing for all team members.

Key points for secure commit signing:

-

Signing keys should be stored and managed by a central secure signing service

-

Private keys must never be exportable to developer machines

-

The signing service should enforce:

-

MFA

-

Device authentication

-

Behavioral analysis and policy checks

-

This ensures every commit is:

-

Authenticated to a real user

-

Cryptographically tied to that user’s identity

…and cannot be forged later by someone who simply compromises a workstation.

Enforce Traceable, Work-Item–Linked Commit Messages

Most repositories allow developers to attach a commit message. This should not be treated as optional free text.

Every code change should map to a clear business or technical need (e.g., feature, bug, requirement). To support this:

-

-

Require commit messages to reference a ticket or requirement ID

-

Use pre-commit hooks, when available, to enforce a standard structure

-

Where hooks aren’t possible, verify this link as part of code review

-

This creates an auditable chain from requirements and defects to specific commits—making it harder for malicious or unexplained changes to slip in unnoticed.

Detecting Attacks: Hardening the Build & CI/CD Pipeline

Even with strong authentication and authorization in place, a sophisticated adversary—or a malicious insider—may still succeed in committing code. The next line of defense is the build and test pipeline.

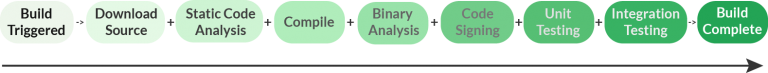

In a typical CI/CD setup:

-

A commit to the repository triggers a build

-

A build server retrieves the latest source code

-

The code is compiled and packaged

-

Automated tests and scans are executed against the binaries (and sometimes the source)

Below are practical measures to detect malicious or unwanted code as early as possible. If you’re worried these will slow your pipeline, remember that post-sign hash validation (from our automated hash validation post approach.) allows you to parallelize and offload many of these checks.

Unit & Integration Testing

Robust unit and integration testing should be employed to ensure that the software functions correctly after every commit. The testing shouldn’t be limited to validating positive scenarios; negative testing should be included at both the unit and integration levels to ensure the code can properly handle unwanted input and behavior. Verification of these tests should also include log analysis to ensure that sensitive data isn’t being logged and errors aren’t being ignored (e.g., by poor practices such as logging and swallowing exceptions).

Static, Dynamic, and Behavioral Scanning

Multiple forms of automated scanning should be embedded into the CI/CD pipeline:,

- Static Application Security Testing (SAST)

- Dynamic Application Security Testing

- Code quality and shape code analysis,

- Antivirus scanning, ..

Third-party tools that can be integrated for different environments include:

- SonarQube,

- Fortify,

- Contrast,

- Visual Studio Analyzers,

- SpotBugs,

- Microsoft Defender, and more,

Fuzzing for Resilience Against Malicious Inputs

Fuzzing Testing should be used to verify that software behaves safely when faced with:

- invalid inputs

- unexpected formats

- randomor adversarial data

At a minimum, fuzzing should ensure that applications do not:

-

Crash

-

Leak memory

-

Trigger assertion failures

-

Enter undefined or unsafe states

Fuzzing can be run alongside unit and integration tests and tied into dynamic analysis for even deeper coverage.

Non-Production Signing for Pre-Review Builds

In most environments, code that has just been committed has not yet passed full review. To limit potential blast radius:

-

Do not sign CI/CD builds with production code signing keys

-

Instead, sign pre-production builds with a test signing key

-

Configure test and staging environments to trust only the test key

Implementation details:

-

For X.509-based signing (Windows, macOS, Java, etc.):

-

Issue the signing certificate from an internal PKI

-

Import the internal CA’s certificate(s) into the trust stores of test systems

-

-

For GPG-based signing (RPM and Debian packages):

-

Import the test GPG public key as trusted on the test systems

-

Even test signing keys should:

-

Be stored in an HSM

-

Be tightly managed and monitored

To minimize exposure:

-

Use a separate internal PKI for code signing, not the same CA that issues machine/user certs across the enterprise.

-

Limit trust for this PKI to only the systems that truly require it.

This design reduces the impact if a malicious build ever gets signed in a non-production environment.

Businesses need a secure code signing system that doesn’t reduce the tempo of day-to-day operations. Learn how to design and deploy such a code signing solution in this post.

Detecting Attacks: The Human Factor in Code Review

Automation is powerful, but it will never catch every advanced, targeted attack—especially those involving nation-state actors or highly skilled insiders. That’s where human code review comes in

We recommend:

-

Every commit destined for a final release should be reviewed by at least one independent, qualified developer

-

Reviews should consider:

-

Correctness

-

Security implications

-

Necessity and scope

-

Code quality and maintainability

-

This is particularly important for mitigating insider threats, where the person inserting malicious code has valid credentials and permissions.

Some teams are hesitant to perform code reviews on all commits because the time it takes to perform the review is considered too costly. However, the cost of a software defect increases the longer the company waits to resolve it, so the code review process is likely less expensive than one might imagine.

Additionally, code reviews are a great way to train new developers joining the team (but the review should also be performed by someone of equal or more senior ranking, whenever possible).

Case Study Lens: Would These Controls Stop Attacks?

With the features above implemented, software suppliers have strong assurances that only code originating from the source code repository will get signed. The next step is to ensure that the code in the repository is “good”. This translates to ensuring that only valid users are making changes to the repository and that the changes that are being made are valid.

We have written about this in detail before but ultimately this boils down to using strong authentication and authorization (e.g., multi-factor authentication, device authentication, commit signing, etc. combined with the principle of least privilege), having every commit reviewed by a qualified reviewer, and scanning the code and resulting binaries with automated tools (e.g., SAST, DAST, fuzzing, etc.). If a source code repository doesn’t support advanced authentication techniques, they can be transparently enforced by using key-based authentication with proxied keys.

The Million Dollar Question

The natural question right now is whether the techniques described in this blog post, as well as the automated hash validation post, would have helped to thwart the recent SolarWinds supply chain attack.

Before we answer that, it’s important to acknowledge:

SUNBURST was a highly sophisticated attack carried out by well-resourced nation-state actors. Many organizations could have been compromised under similar conditions.

We reference it here purely because it is a well-documented, relevant example—not to suggest specific shortcomings in SolarWinds’ internal processes.

What We Know About SUNBURST

First, let’s state some important facts we know about the SolarWinds attack (thanks to the great write-ups by ReversingLabs and FireEye, as well as the information provided by SolarWinds):

- The attackers were able to get the build process to sign something that didn’t match what was in the repository.

- The source code for the malware was formatted in a manner consistent with the rest of the codebase.

- The source code for the malware contained Base64 encoded compressed strings.

- The source code for the malware contained unusual components for a .NET application such as references to kernel32.dll, using WMI to enumerate system information, enumerating and tampering account privileges, tampering with system shutdown, and more.

- The binaries were signed within a minute of being compiled.

- The malware stayed dormant for up to two weeks before retrieving and executing commands.

- The malware used multiple obfuscated blocklists to identify and evade forensic tools and antivirus software.

Impact of Automated Hash Validation

With automated hash validation in place:

-

Pre-sign validation would simply refuse to sign mismatched binaries

-

Post-sign validation would quickly flag signatures on binaries whose hashes didn’t align with the repository state

In either case, the discrepancy between the committed source and what was signed would be detected or blocked.

What If Attackers Did Manage to Commit Malicious Code?

For educational purposes, assume a different scenario in which attackers do get their malicious code into the repository.

With the strong authentication patterns described earlier, this would require either:

-

Compromising a trusted device, plus first- and second-factor credentials, plus evading behavioral analytics, or

-

Receiving help from an insider with legitimate access

Once committed, the build server would request a signing operation, triggering automated hash validation. In this scenario:

-

The validation step would confirm that the to-be-signed hash matches the repository state

-

No mismatch would be detected at this stage, because the malicious code is now “legitimate” from the repository’s point of view

At that point, detection depends on:

-

Scanners and analyzers

-

Automated tests

-

Human code review

Given public information:

-

It is unclear whether existing scanners would have caught SUNBURST immediately; many vendors updated signatures after the incident became public.

-

Facts #2 and #3 suggest the malware’s source was stylistically blended but contained encoded strings and unusual API usage, which would be suspicious to a trained reviewer.

Automated testing and fuzzing likely would not have triggered the payload:

-

Facts #6 and #7 suggest delayed activation and environment-aware evasion.

-

Activation may have depended on system time, network conditions, registry values, or external services (e.g., NTP), which are not typically replicated in CI/CD test environments.

That leaves code review as the last line of defense. A qualified reviewer, seeing:

-

Hardcoded Base64-encoded strings

-

Kernel32 and WMI usage in an unexpected context

-

Privilege tampering logic

…would have strong reasons to question and block such changes. If malicious code still passed review, it would most likely be due to:

-

Insufficiently thorough reviews, and/or

-

Collusion by multiple insiders participating in the review process

Summary of Impact

-

Because the actual SolarWinds compromise occurred in the build environment, not in the repository, automated hash validation would likely have prevented or quickly exposed it.

-

With all the controls described in this article:

-

It becomes extraordinarily difficult for an attacker to inject malware into the repository and get it signed with a production key without help from insiders.

-

To be absolutely clear:

Garantir has no reason to believe, and is not suggesting, that any SolarWinds employee knowingly assisted the attackers or had prior knowledge of the attack.

The analysis above is hypothetical and based on how automated hash validation and strong repository controls would behave under similar conditions.

Next Steps: Beyond the Build

So you’ve implemented automated hash validation, tightened authentication and authorization, embedded scanning and fuzzing into CI/CD, and mandated code review for every release commit.

Are you done?

Not quite.

All of these controls are critical, but they primarily secure the build and signing pipeline. To fully secure the software lifecycle, you must also:

-

Protect delivery channels for software and updates

-

Secure installation and update mechanisms

-

Ensure runtime environments validate signatures correctly and enforce policy

-

Consider attestation and provenance verification at deployment and runtime

Code signing is powerful, but it has no value if clients don’t properly verify signatures—or if they trust the wrong keys.

.

How GaraTrust Helps

If you’re looking to harden your build and signing process with the techniques described here, Garantir can help.

GaraTrust:

-

Implements automated hash validation for code signing

-

Secures private keys in HSMs or enterprise key managers

-

Supports strong authentication to source control and other endpoints

-

Enables enforcement of:

-

Multi-factor authentication

-

Device authentication

-

Approval workflows

-

Just-in-time access

-

Fine-grained policy per user and per key

-

—all while allowing teams to continue using the same tools and workflows they rely on today.